Introduction

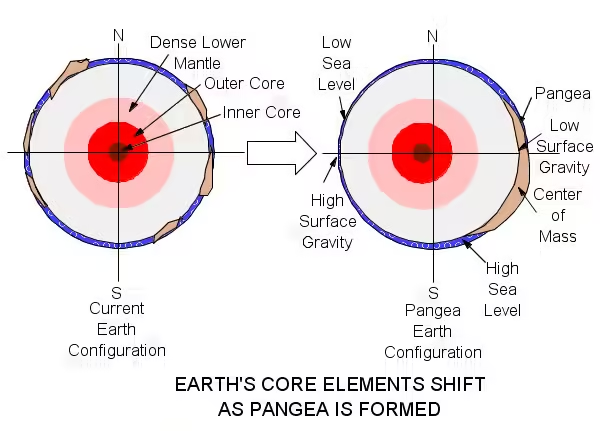

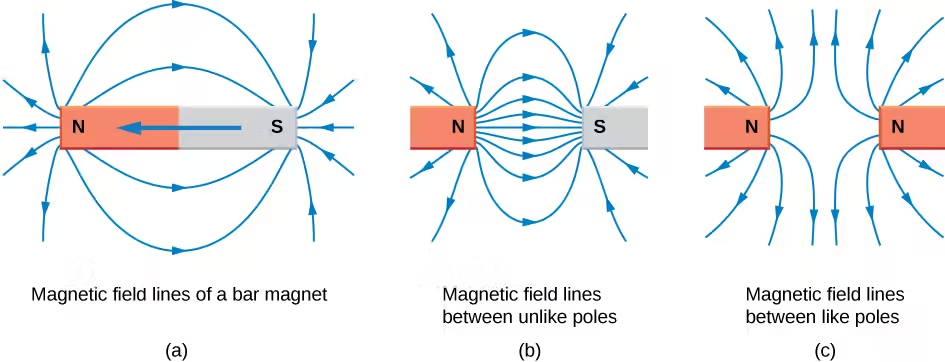

Earth’s magnetic field is an invisible force surrounding the planet, generated by the movement of molten iron in the outer core. It functions like a massive bar magnet, with north and south magnetic poles, producing magnetic lines that curve outward from one pole, loop around the planet, and re-enter at the opposite pole. Similar to a bar magnet, the field is strongest at the poles and weaker near the equator. This magnetic shield protects Earth from harmful solar radiation and plays a key role in guiding navigation systems, including compasses.

North and South Magnetic Pole

Attribution: DMY, CC BY 3.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Page URL: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/

- The North and South magnetic poles are points where Earth’s magnetic field lines converge at the South Pole and diverge at the North Pole, serving as the poles of the planet’s magnetic field. These differ from the geographic poles, which are fixed points marking where Earth’s axis of rotation intersects its surface.

- Magnetic poles are not stationary and can shift over time due to Earth’s molten core changes. The North Magnetic Pole, currently in the Arctic region, moves several kilometers yearly.

- Geographic poles remain fixed, representing the points at 90o latitude North and 90o latitude South where Earth’s axis of rotation meets its surface.

- The magnetic poles are the points toward which a compass needle aligns and are key elements of Earth’s magnetic field.

- The geographic poles mark Earth’s axis of rotation and are essential for determining latitude, setting time zones, and guiding global navigation systems.

- The magnetic poles can reverse in a phenomenon known as Magnetic Reversal, where the North Magnetic Pole becomes the South Magnetic Pole and vice versa. These flips occur over thousands or even millions of years. In contrast, the geographic poles remain unchanged.

Magnetic Reversal

Earth’s magnetic poles occasionally swap positions over geological timescales in a process called magnetic reversal. During this, the North Magnetic Pole becomes the South Magnetic Pole and vice versa. These reversals occur irregularly, approximately every 200,000 to 300,000 years, though their exact timing is unpredictable.

Magnetic reversal occurs due to changes in the flow of molten iron within Earth’s outer core, which generates the planet’s magnetic field. As this flow becomes unstable over time, the magnetic field weakens, causing the poles to drift. Eventually, the field may flip, leading to a reversal in polarity.

Geologists have uncovered the pattern of magnetic reversals by studying magnetic minerals in ancient rocks. As lava cools, these minerals align with Earth’s magnetic field. Once the rock solidifies, the minerals preserve the direction of the magnetic field at that time, enabling scientists to track past reversals.

Studies of the ocean floor reveal a pattern of magnetic stripes that alternate in polarity, reflecting past magnetic stripes that alternate in polarity, reflecting past magnetic reversals. These strips are aligned with the spreading of tectonic plates, providing further evidence of Earth’s magnetic history.

Magnetic reversals occur gradually over thousands of years, not abruptly. During a reversal, Earth’s magnetic field weakens, but there’s no evidence to suggest it causes mass extinctions or significant climate changes. However, it could temporarily affect navigation systems and slightly increase radiation exposure.

How the Earth’s Magnetic Field Works

Earth’s magnetic field generates the magnetosphere, a vast region surrounding the planet. This area deflects and traps charged particles from the solar wind, stopping them from directly reaching Earth’s surface. Stretching thousands of kilometers into space, the magnetosphere functions like a protective force field.

Page URL: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki

When the solar wind reaches Earth, the charged particles are guided by the magnetic field. Instead of striking the planet directly, they are redirected along the magnetic field lines toward the polar regions. This happens because charged particles are forced to spiral along the magnetic lines rather than passing straight through them.

Inside the magnetosphere are two donut-shaped regions known as the Van Allen radiation belts. These belts trap high-energy particles from the solar wind, stopping them from reaching Earth’s surface. By absorbing and containing radiation, the Van Allen belts provide additional protection for life on the planet.

Attribution: OpenStax, CC BY 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Page URL: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/

When some solar particles reach Earth’s atmosphere, they are directed toward the magnetic poles, where they collide with gases in the upper atmosphere. These collisions produce stunning light displays known as auroras or the Northern and Southern Lights. While these displays are mesmerizing, they also serve as a reminder of Earth’s magnetic field in action, diverting harmful solar particles away from the majority of the planet’s surface.

Without Earth’s magnetic shield, the solar wind could gradually erode the atmosphere, similar to what happened on Mars, which lacks a strong magnetic field. This would leave Earth vulnerable to harmful ultraviolet (UV) radiation, which can damage DNA, disrupt ecosystems, and make the planet much less hospitable for life.

The Roles of Earth’s Magnetic Nature

Compasses function by aligning with Earth’s magnetic field, specifically pointing toward the magnetic north, the direction of the North Magnetic Pole. A magnetized needle inside the compass rotates freely and naturally aligns with Earth’s magnetic field lines, with one end to magnetic north.

Attribution: OpenStax, CC BY 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Page URL: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/

Magnetic north is different from geographic north, and this difference is known as magnetic declination. Despite this distinction, compasses have been vital for navigation for centuries, enabling people to find direction by utilizing Earth’s magnetic field.

Electrical power grids can be disrupted by geomagnetic storms caused by solar flares. These storms induce electric currents in power lines, potentially overloading transformers and causing widespread power outages.

Satellite communications and GPS signals can be disrupted when solar particles interfere with Earth’s magnetosphere, distorting radio waves. High-frequency (HF) radio signals, used for aviation and military communication, are particularly vulnerable to interference.

Magnetometers in smartphones, which help apps like Google Maps find your direction, can act up during magnetic disturbances. These sensors pick up Earth’s magnetic field to figure out where you’re going, but if there are sudden changes or interference, it can throw off the accuracy of the readings.

Conclusion

Understanding Earth’s magnetism is crucial for appreciating its role in both protecting life and supporting modern technology. The magnetic field acts as a protective shield against harmful solar radiation and cosmic particles, safeguarding our atmosphere and enabling life to thrive. By deflecting solar wind and trapping charged particles in the Van Allen belts, the magnetic field prevents severe radiation from reaching Earth’s surface, thus maintaining a stable environment for living organisms.

Share the knowledge with