Introduction

The term “black hole” is of very recent origin. In 1969, there were two prevailing theories about light. One proposed that light was composed of particles, while the other suggested it was made of waves. Under the wave theory, the interaction of light with gravity was not well understood. However, considering light as particles made the interaction with gravity more comprehensible. Based on this idea, John Michell wrote a paper in 1783 in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. In it, he proposed that a star sufficiently massive and compact would have such a strong gravitational field that even light could not escape. Such objects are what we now call black holes.

The above picture is a fictional graphical representation of actual black holes

Formation of Black Holes

The formation of black holes is not a one-day story but a whole process. To understand the beginning of a black hole, we need to know about the life cycle of a star.

When a large amount of gas (mostly hydrogen) starts to collapse in on itself due to its gravitational attraction, a star is formed. As it contracts, the atoms of the gas collide with each other more and more frequently and at greater speeds. Over time, as the density increases, the gas heats up. Eventually, the gas becomes so hot (nearly 1,000,000,000 K) that when the hydrogen atoms collide, they no longer bounce off each other but instead merge to form helium atoms. This process is called hydrogen burning. Because of this, the helium abundance in first-generation stars is much greater than in later generations.

The heat released in this reaction, which is similar to a controlled hydrogen bomb, is what makes stars shine. This heat also increases the pressure of the gas until it is sufficient to balance the gravitational attraction. Stars will remain stable in this state for a long time, with the heat from the nuclear reactions balancing the gravitational attraction. Eventually, the star will use up its hydrogen and other nuclear fuels. When the star runs out of fuel, it will start to cool off and contract.

Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar, an Indian-American theoretical physicist, proposed that when a star becomes very small, the matter particles come very close to each other. According to the Pauli exclusion principle, two matter particles cannot have both the same position and the same velocity. Chandrasekhar calculated that a star with a mass greater than about one and a half times that of the Sun would be unable to support itself against its own gravity once it has exhausted all of its fuel. This limit is known as the Chandrasekhar limit.

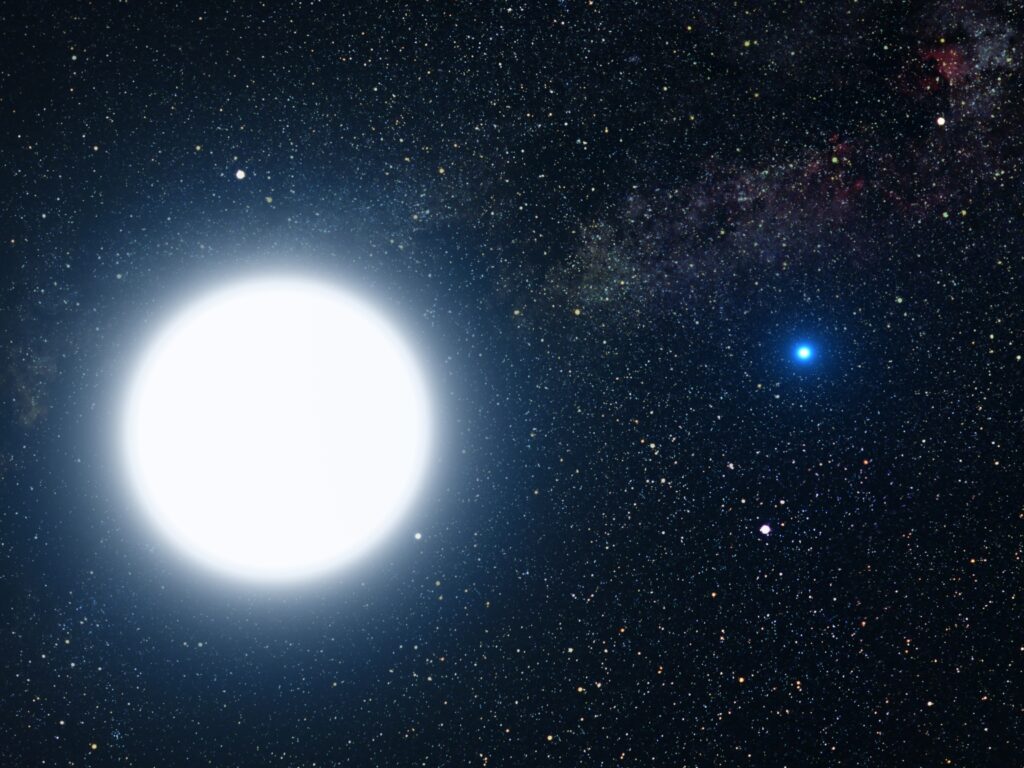

If a star’s mass is less than the Chandrasekhar limit, it can eventually stop contracting and settle into a stable final state as a white dwarf. A white dwarf has a radius of a few thousand miles and a density of hundreds of tons per cubic inch.

White dwarf

If a star has a mass four to five times the Chandrasekhar limit, gravitational collapse will lead to a supernova explosion, causing the outer layers of the star to be expelled into space. After the supernova, the remaining core will collapse into a region of space with such intense gravitational attraction that light cannot escape, forming a black hole.

Graphical representation of black hole

Will our sun convert to a black hole?

Pingback: What is the Supernova Explosion? What Happens During a Supernova?