“I think I can safely say that nobody understands quantum mechanics,” ~ Richard Feynman.

What is Quantum Physics?

Quantum physics is the study of the smallest things in the universe, like atoms, electrons, and photons. Quantum physics explains how particles behave on the smallest scales. Traditional physics (Newtonian mechanics) can’t explain what happens at these tiny levels, so quantum mechanics steps in with a more accurate picture of reality. It shows us why electrons orbit around nuclei, how light can act like both a particle and a wave, and why matter exists in specific energy states. Understanding quantum physics is key to making sense of how the physical world works at its most fundamental level.

Quantum physics is incredibly important because it changes how we understand reality, drives new technology, and pushes the limits of what we know. Its influence stretches across science, technology, and philosophy, making it a key part of modern thinking and innovation.

Understand Quantum Physics

Quantum physics is based on a few key ideas that help us understand its complex nature. Despite its tricky concepts, these core principles provide a stable foundation. For example, superposition allows particles to be in multiple states at once, and entanglement connects particles in ways that classical physics can’t explain. These basic ideas are crucial for making sense of the quantum world and for applying its discoveries to technology and science.

Wave-Particle Duality:

- In the double-slit experiment, when light or particles pass through two slits, they create a pattern of alternating light and dark bands on a screen behind the slits. This pattern shows that the particles are acting like waves, overlapping and interfering with each other to create the distinctive pattern.

- Similarly, when waves hit an obstacle or pass through a slit that’s about the same size as their wavelength, they bend around it and spread out. This spreading pattern, known as diffraction, is another sign that the waves are behaving like waves.

- When light shines on a metal surface, it can cause electrons to be ejected from the metal. This happens because light acts as particles, called photons, that transfer energy to the electrons. This phenomenon, known as the photoelectric effect, shows that light behaves as discrete packets of energy rather than just a continuous wave.

The way a particle behaves depends on the type of experiment you’re conducting. If the experiment tests wave properties, like interference, the particle will act like a wave. But if the experiment focuses on discrete interactions, like the photoelectric effect, the particle will behave like a particle.

Niels Bohr’s Principle states that wave and particle descriptions are two sides of the same reality. According to Bohr, these two views provide different but complementary perspectives on how quantum entities behave. To fully understand quantum phenomena, both descriptions are needed.

Quantum Superposition:

- In quantum mechanics, a particle’s state is described by a mathematical tool called a wave function. This wave function gives a full description of the particle’s properties, including its position, momentum, and energy.

- In quantum theory, a particle’s wave function can be a blend of multiple possible states, known as superposition. For example, an electron can be in several energy levels or positions at the same time.

- Superposition leads to quantum interference, where the likelihood of different outcomes changes because of the wave-like behavior of particles. This can create patterns of constructive or destructive interference, like the ones seen in the double-slit experiment.

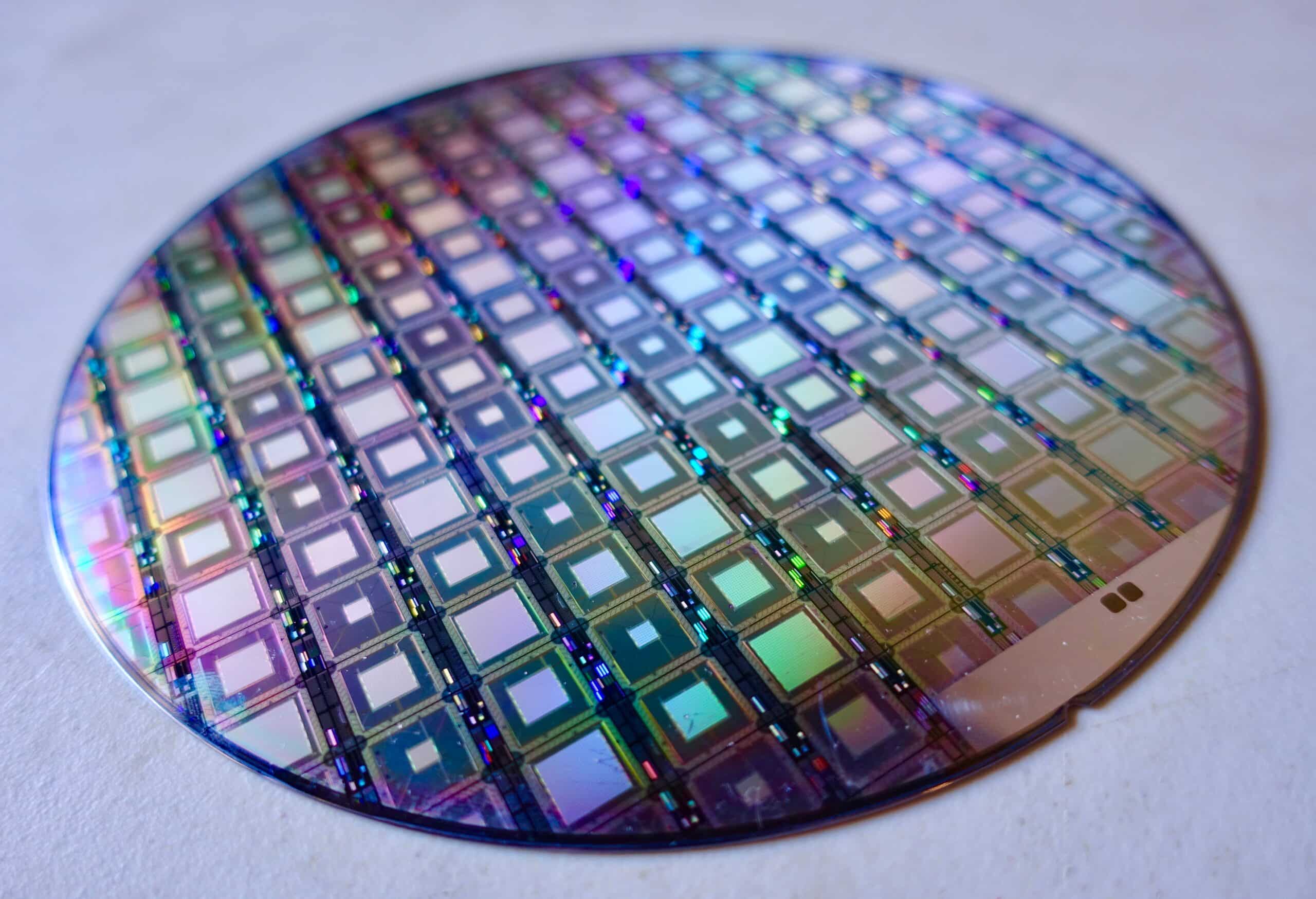

- In quantum computing, superposition lets quantum bits (qubits) represent multiple states at the same time. This ability allows quantum computers to perform many calculations simultaneously, greatly boosting their computing power.

Quantum Entanglement:

- When particles become entangled, their quantum states are linked, so you can’t describe one particle’s state without also describing the other particle(s)’ state. This connection remains even if the particles are far apart.

- Entangled particles share a combined quantum state, and measuring one particle immediately affects the state of the other, regardless of the distance between them.

- When you measure one particle in an entangled pair, it instantly determines the state of the other particle. For instance, if you measure the spin of one particle and find it to be up, the spin of the other particle will automatically be down, no matter how far apart they are.

- Even though entanglement creates instant correlations between particles, it doesn’t allow for faster-than-light communication or information transfer. The results of measurements are random, so while the states of entangled particles are linked, no actual information travels faster than light.

Historical Background of Quantum Physics

- 1900: In 1900, Max Planck introduced the revolutionary idea of quantization to solve the “ultraviolet catastrophe” in blackbody radiation. Instead of energy being emitted continuously, he proposed that it is released in small, discrete packets called quanta. This breakthrough marked the beginning of quantum theory and ultimately earned Planck the Nobel Prize in 1918.

- 1905: In 1905, Einstein built on Planck’s idea to explain the photoelectric effect—the release of electrons from metal when exposed to light. He suggested that light is made up of particles called photons, each carrying a specific amount of energy. This discovery showed that light has a particle nature, and it earned Einstein the Nobel Prize in 1921.

- 1913: Niels Bohr developed a model of the atom that used quantum ideas. His Bohr Model proposed that electrons orbit the nucleus in fixed energy levels and can move between them by absorbing or emitting specific amounts of energy. This explained the quantum nature of atomic spectra.

- 1924: In 1924, de Broglie proposed the groundbreaking idea of wave-particle duality, suggesting that particles such as electrons could behave not only like particles but also like waves. This revolutionary concept was later confirmed through experiments and became a fundamental principle of quantum mechanics. For his contributions, de Broglie was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1929.

- 1925: Heisenberg developed matrix mechanics, the first complete version of quantum mechanics. In 1927, he introduced the Uncertainty Principle, which states that it’s impossible to precisely know both the position and momentum of a particle at the same time. This groundbreaking work earned Heisenberg the Nobel Prize in 1932.

- 1926: In 1926, Schrödinger developed wave mechanics, describing particles as wave functions governed by the Schrödinger equation. This mathematical framework became a powerful tool for predicting the behavior of quantum systems and complemented Heisenberg’s matrix mechanics. Schrödinger’s contributions earned him a share of the Nobel Prize in 1933.

- 1927-1930: Dirac made major contributions to quantum theory, especially with his development of quantum electrodynamics (QED) and the Dirac equation, which describes the behavior of relativistic electrons and predicted the existence of antimatter. His groundbreaking work earned him the Nobel Prize in 1933.

- 1920s: The Copenhagen Interpretation, largely developed by Bohr and Heisenberg, is the most widely accepted philosophical approach to quantum mechanics. It proposes that quantum systems don’t possess definite properties until they are measured. Instead, they exist in a state of probabilities, and it is the act of observation that causes these probabilities to collapse into a specific outcome. This interpretation underscores the crucial role of the observer in determining the state of a quantum system.

- 1935: Einstein, Podolsky, and Rosen proposed the EPR paradox to challenge the completeness of quantum mechanics by introducing the concept of quantum entanglement. They aimed to show that quantum theory was incomplete, arguing that it couldn’t fully describe physical reality. However, their paradox led to deeper exploration of entanglement, which has since become a fundamental aspect of quantum theory.

- 1964: John Bell developed Bell’s Theorem, which offered a way to test whether quantum mechanics could be explained by local hidden variables, as Einstein had hoped, or if quantum entanglement actually defied classical ideas of locality. Experiments based on Bell’s Theorem confirmed the non-locality of quantum mechanics, validating the reality of entanglement and showing that quantum effects can’t be explained by local hidden variables alone.

- 1940s-1960s: The development of Quantum Field Theory (QFT) and the formalization of Quantum Electrodynamics (QED) created a unified framework for understanding the interactions between light and matter. Richard Feynman, Julian Schwinger, and Sin-Itiro Tomonaga were awarded the Nobel Prize in 1965 for their pioneering work in QED.

Quantum physics, with its groundbreaking ideas and often surprising conclusions, gives us a deep and sometimes counterintuitive view of the nature of reality. Starting with Max Planck and Albert Einstein, who laid the groundwork, and continuing with Niels Bohr, Werner Heisenberg, and Erwin Schrödinger, the field of quantum mechanics has evolved significantly. It constantly challenges classical ideas and broadens our understanding of the microscopic world.

Pingback: How Quantum Computing Will Redefine Our World?